In July 2023 Italy had declared its intention to quit the Chinese-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Although Italian Prime Meloni has yet to issue a final verdict in December, she has spoken out against the project at several occasions. This leads analysts to believe that Italy will leave the BRI framework – a fast change from joining only in 2019. Naturally, at the heart of this shift lies economics. Italy had hoped to receive a far larger investment than it actually received. China has invested $24bn since 2005, although only $1.83bn has been invested into the country since joining the BRI in 2019 – dropping to a total investment of $33m in 2021. China has also disproportionately benefitted from this investment, allowing the nation to grow Chinese exports to Italy from €33.5bn to €50.9bn – whilst Italy only saw an increase from €14.5bn to €18.5bn (Source: CFR, 2023). This experience suggests that joining the BRI does not automatically garner large-scale investments, as commonly seen recipients such as Pakistan, Indonesia or even Hungary.

What is the Belt and Road initiative?

The Belt and Road Initiative is a name reminiscent of the historical Silk Road trade route between Europe and China. The Chinese government is using this as a major geopolitical strategy to develop railroad and pipeline infrastructure, deep water ports, energy production, loans and resource exploration. This initiative is split between the land-focused Silk Road Economic Belt and Economic Corridors, and the Maritime Silk Road – with the latter attracting the bulk of Chinese investments.

Italy serves as an end-point to the Maritime Silk Road, before it joins the European network of rivers. For this reason, Xi has courted Italy to better prepare the country to receive Chinese exports, which have the potential to flow into Europe’s common market and feed into other Chinese investments in Europe.

How widespread is the BRI?

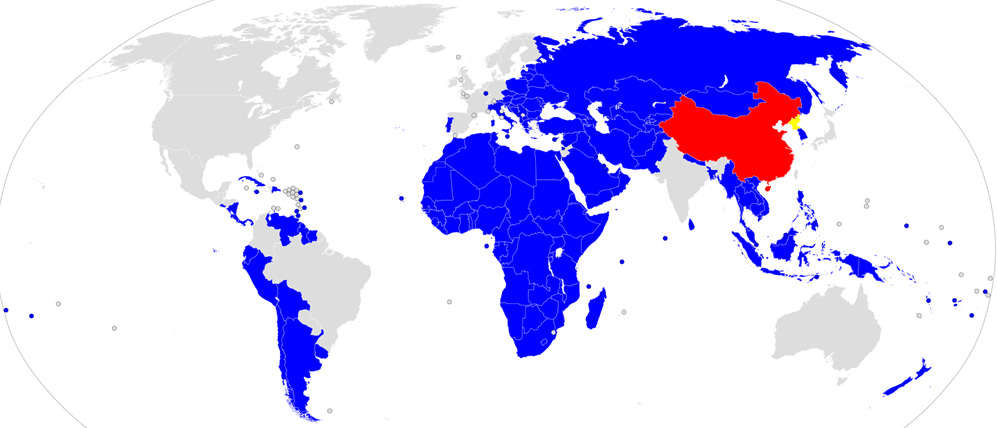

As of August 2023, 155 countries are involved in the BRI, as reported by the Chinese Government. These participant countries account for over 75% of the world’s population and over half of the world’s GDP. The investment to each region varies wildly each year. The investments for 2022 are as follows: East Asia (34.53%), West Asia (3.91%), Sub-Saharan Africa (9.14%), Middle East (20.90%), South America (8.13%) and Europe (23.39%) (Source: GreenFDC, 2022). With the exception of North America, this represents a significant level of investment around the world. London-based CEBR suggest that BRI is likely to increase world GDP by $7.1 trillion per year by 2040, leading to real incentives for countries to join. This beckons the question of why Italy is motioning to exit BRI if China is heralding worldwide economic growth.

Why is Italy leaving?

Meloni has described the Italian involvement in the BRI as a paradox, as it was the only G7 country that was a member to the agreement – yet did not have the strongest trading links. Instead, Italy remains as the G7 member state with the lowest monetary amount of total trade with China - beckoning the question of what the BRI membership has achieved for Italy. The previous populist-leaning government in Italy may also have made the move to join the BRI as a way to reduce dependence on the EU, which Rome has since criticised as an “improvised and atrocious act”, which is not necessary to develop partnerships with China, yet subjects Italy to much more influence from Beijing.

Italy has also criticised the agreement due to a string of security concerns. For instance, the Italian Parliament has raised concerns that the agreement will present security risks in infrastructure, finance and telecoms. These concerns have been shared with the EU and the USA, leading to Chinese companies such as Huawei being blocked from working with Telecom Italia on a contract to supply 5G equipment. Suspicions within the EU have caused for member states such as Belgium to opt for European companies like Nokia to supply key telecoms equipment amongst mounting US pressure. Refusing additional BRI investments may be seen as an extension of security policy in this case.

Will other countries follow?

China’s focus on Chequebook diplomacy has forced BRI states to make concessions to the country when they have been unable to repay large debts. For instance, The Hambantota International Port in Sri Lanka is the second largest deep water port in the country, after Colombo, and has now been leased to China on a 99-year lease, with potential for another 99-year extension. These practices have granted China hard power, and significant influence abroad which allows the BRI to continue to develop internationally. The US and EU do not have clear alternatives to such an initiative, driving many countries towards China for investments, with the nation becoming the largest creditor nation in the world.

Developments from Italy may convince other Maritime Silk Road and BRI countries to reconsider their involvement with China. However, Italy was never as deeply involved in the project as other states and as such has the potential to withdraw without risking both diplomatic and economic relationships with China. For this reason, existing economic commitments act as determining factors regarding a nation’s future with the BRI, which has been the whole reason for China to massively invest into its neighbours.

Hungary has benefitted from huge levels of Chinese foreign investment since joining the BRI in 2015. In the same year Hungary became the largest recipient of Chinese investments ($571m). In 2022 this ballooned into $7.6bn, featuring an investment from Chinese battery company CATL to build a factory in Debrecen. The country also hosts the largest Huawei supply centre outside of China, and echoes Chinese political policy. For example, Orbán has formally blocked the EU from formally criticising Chinese actions in Hong Kong in 2020 and 2021, and has supported the Chinese peace plan regarding the Russia-Ukraine War in 2023. Such relationships demonstrate that Chinese investment into Hungary has returned dividends in the form of political support, and division within the EU. There is little foreseeable reason for the BRI to seize investment into Hungary when the relationship has proven to be so profitable for both governments.